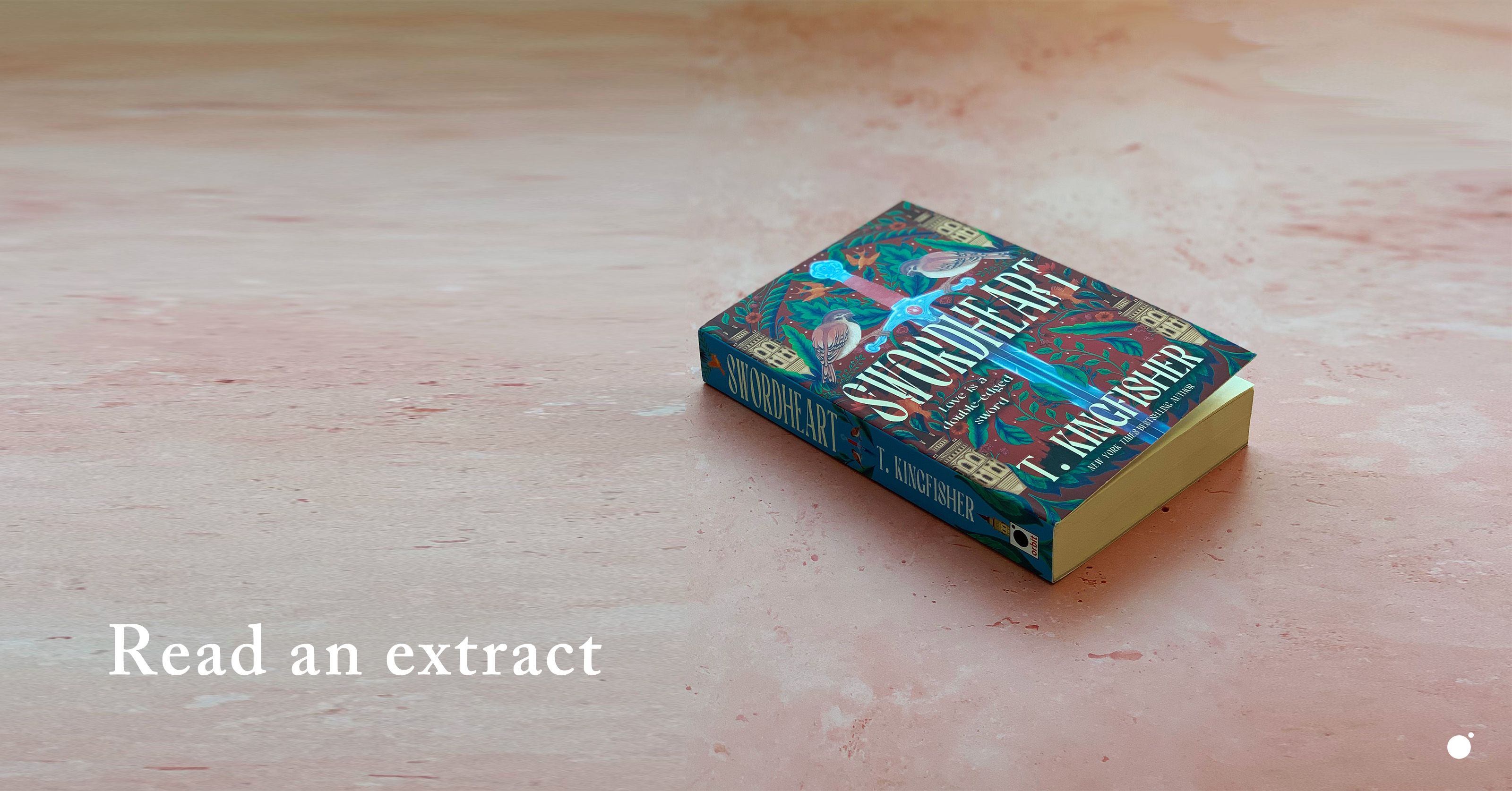

Read an extract from Swordheart by T. Kingfisher

Introducing your new favourite cosy fantasy romance.

Open the pages of Swordheart by T. Kingfisher if you are looking for a cosy romance featuring a brazen housekeeper and a warrior trapped inside a magical sword. The perfect read for fans of Legends and Lattes, Nettle and Bone and Naomi Novik.

‘Absolutely delightful and full of charm and truth’ Naomi Novik, on Thornhedge

Halla has unexpectedly inherited the estate of a wealthy uncle. Unfortunately, she is also saddled with money-hungry relatives full of devious plans for how to wrest the inheritance away from her.

While locked in her bedroom, Halla inspects the ancient sword that’s been collecting dust on the wall since before she moved in. Out of desperation, she unsheathes it?and suddenly a man appears. His name is Sarkis, he tells her, and he is an immortal warrior trapped in a prison of enchanted steel.

Sarkis is sworn to protect whoever wields the sword, and for Halla?a most unusual wielder?he finds himself fending off not grand armies and deadly assassins but instead everything from kindly-seeming bandits to roving inquisitors to her own in-laws. But as Halla and Sarkis grow closer, they overlook the biggest threat of all? The sword itself.

Scroll down to read an extract.

CHAPTER ONE

Halla of Rutger’s Howe had just inherited a great deal of money and was therefore spending her evening trying to figure out how to kill herself.

This was not a normal response to inheriting wealth. She was aware of that. Unfortunately, she didn’t seem to have many other options. She had been locked in her room for three days and the odds of escape, never good, were growing increasingly slim.

Her relatives were going to be the death of her.

She had always believed that this was true in a metaphorical sense. Her two aunts and her assorted cousins would have tried the patience of a paladin or a saint. It was only in the last two days that she’d realized it was probably true in a literal sense as well.

Halla rested her forehead against the diamond- shaped glass in the window. Uncle Silas had been reasonably wealthy, partly because he never spent a single penny he didn’t have to. All the windows were made of many tiny panes, inexpensive to replace if one was broken. He would have used oiled paper if he could have gotten away with it, like the poorest houses in the village, but as he aged, the damp got into his joints. When not even a roaring fire could drive it away, he finally gave up and put glass in the windows.

It was cheap glass, full of bubbles. The reflection it threw back to her was distorted, so she could see only an oval of pale skin, pale hair, and respectably dark mourning clothes.

She wished Silas had spent more on glass and saved less. Or at least had the decency to leave the money to his other family members, and not to her.

The look of shock on Aunt Malva’s face when the village clerk had read out the will had been gratifying for an instant. Then the rest of Silas’s family had turned to stare at her and it had sunk into Halla’s brain that her great- uncle had really and truly left everything to her.

He’d probably thought he was doing her a favor.

Now I have something they want, and they can only get it by going through me.

Married or buried, I suspect it’s all the same to them. So long as the marriage comes first.

Cousin Alver had proposed that first evening. She rebuffed him, claiming that she was still much too distraught to think of any such things. The conversation hadn’t gone well after that. “Your husband is long gone,” said Aunt Malva, setting her knife down on the table with a click. “You cannot possibly still be in mourning for him!”

Halla narrowed her eyes and set her own fork down. “My great-uncle passed away yesterday, madam!”

Aunt Malva flushed. Her skin was whited with powder to an unnatural shade, which matched the whitewash on the walls. It made her flush of anger all the more vivid, coming out in red blotches around her eyes and her ears where the powder hadn’t quite gone on correctly.

Great-Uncle Silas had not believed in wasting money on table-cloths, even if it made the kitchen look like a poor crofter’s hall, so Malva’s hands were very white against the dark wood of the table. She reminded Halla of a ghost or a ghoul.

Mostly a ghoul. Coming along to gnaw the corpse before Silas is even cold.

Hmm, perhaps a ghoul would prefer a warm corpse, now that I think about it. Maybe it’s like fresh bread out of the oven, if you’re a ghoul.

“Well,” said Aunt Malva. “I suppose I am simply surprised that anyone would mourn Silas, that’s all.”

“Mother,” said Cousin Alver quietly.

“I’ll speak the truth, Alver! I always do, no matter how it costs me. Silas was a strange, wretched, tightfisted old man, with no proper affection for his kin or clan.”

“He is not even in the ground,” said Halla, abandoning her thoughts about ghoul diet. “And he was very kind to me when I was young.”

“And even kinder now that you aren’t!”

“Mother.”

“In fact— ” Malva began, and then a guttural voice interrupted her.

“Into the pit, the pit, the black pit, when the souls scream and the worms coil . . .”

Halla seized on the excuse gratefully and rose to her feet. “You’ve upset the bird,” she said.

The bird in question was a small, finch-like creature that could have perched easily on Halla’s smallest finger, had she been foolish enough to stick her finger in its cage, which she wasn’t. It had a red beak and red eyes and most of the time it sang a repetitive three-note song that went, “tweedle-tweedle-twee!” Occasionally, its eyes would flash green and it would begin roaring in an impossibly deep voice about the end of the world and the screams of the damned.

Great-Uncle Silas had been extraordinarily fond of it. Two priests and a paladin had certified that it wasn’t possessed by a demon, although they also all said that there was clearly something very wrong with it and had recommended a great deal of fire followed by a great deal of holy water. Silas had instead put it in a cage in the dining room, because he was that sort of person.

“Hush,” said Halla, pulling the tray with the bird’s food out. It was built so that you never had to put your hand inside the cage. She took a bit of chicken off her plate and put it in the tray, then slid it back in. The bird leapt on it, cackling in a voice like a very old man heard through a drainpipe.

“Nasty creature,” said Aunt Malva.

Normally Halla would have agreed with her, but she didn’t want to give the woman any satisfaction. “Silas was fond of it,” she said.

“Silas was fond of a great many useless things,” said Malva, giving her a look that left no doubt who she was referring to.

“If you’ll excuse me,” said Halla, “I find I have no appetite.” She stalked from the room, angry and shaken and secretly relieved that she had a perfectly good excuse to flee from Alver and his mother.

Cousin Alver had caught her on the stairs. She might have felt the smallest twinge of respect for that, except that she had clearly heard, as the door swung shut, Aunt Malva saying, “Well? Go after her!”

You know that she is wrong, but you feel no need to smooth things over unless she orders you to do it.

“Halla,” he said from the bottom of the staircase. He curled his hands around the banister. He wore large gold rings set with stones. The servants said he never took them off, not even to bathe or sleep, and Halla knew that the skin around them was always clammy with sweat.

She could imagine, far too easily, those clammy, ringed hands on her skin. Her stomach turned over and she was glad that she hadn’t eaten much.

“Halla, my mother doesn’t mean the things she says. She just wants what’s best for you.”

“She means every word,” said Halla. “It’s just a shock to her that I’m not her nephew’s penniless widow any longer.”

Cousin Alver gripped the knob at the base of the banister, not looking at her. “You know she’s always been fond of you.”

“She’s got a damned strange way of showing it!”

“Yes, she does.” His voice was so dry that for a minute Halla was forced into unwilling sympathy with him. However hard it was to deal with Aunt Malva in small doses, being her son was probably an entirely different circle of hell. Then he destroyed that instant of sympathy by saying, “She’ll be better if there are children. She’s always been very good with children.”

“I have not agreed to your proposal!”

“Well.” Cousin Alver still didn’t meet her eyes. “We’ll discuss this tomorrow, when you’re less tired.”

Halla wanted to be the sort of person who yelled at her cousin and forced him to acknowledge that she had a choice in the matter. Unfortunately, it seemed that she was the sort of person who ran up the stairs to her bedchamber, grateful for the reprieve. This was a depressing discovery.

But not, I suppose, an unexpected one.

At least I am the sort of person who slams the door. That’s worth something.

She collapsed on her bed, the echoes of the slam still ringing through the house.

The money was useless to her. She knew that she would never be allowed to touch it. They would marry her to Alver and take it away so that it stayed in the family and everything would be just as it had been, except worse because Alver was alive and Silas was dead.

Why couldn’t it be Alver who was old and had bad lungs? Why couldn’t he have died instead?

Well, but if Alver was old then he wouldn’t be looking to marry me, and presumably there’d be someone else to fill the Alver-shaped hole in the world, and I’d be right back here except with a different obnoxious person trying to wed me.

Although at least that person might not have clammy hands.

She got up and stared out the window into the dark, thinking about all the ways a woman could die.

Even if her cousins did not actually poison her or push her down the steps, there were many ways to make an unwanted relative’s life shorter. Medicines administered for her “health” that left her docile as a milch cow. Wonderworkers whose talents ran to harm.

Childbirth.

Halla shuddered.

Her late husband hadn’t awoken any great passions in her, but at least he hadn’t made her skin crawl. They had gotten along tolerably well for a few years, until a late spring fever had swept the land and carried him off. His estate had gone to his brother and Halla had found herself nearly penniless after the death duties.

A young widow, she might have remarried if she were wealthy, but there was no market for widows of no particular wealth and no particular beauty. Her mother’s family was far too poor to be burdened with another mouth to feed. Her husband’s great-uncle, Silas, had taken her in and she had become a middle-aged widow in his house, running the household and seeing that his old age was as comfortable as she could make it.

He had been a strange, erratic, maddening man, but she had always been grateful. He put up with her, and Halla knew that could be difficult.

She knew that he had saved her from the convent, or worse. There was a click at the door. She knew without turning that someone had bolted the door to her chamber.

It seemed that worse had finally caught up with her.